Winged Corn

Roundup, Bayer, the homogeneity of our food system, and how it all ties into ICE

I’ve had this story rattling around in my head for a month. It’s one of those tales that once you hear it you wonder why doesn’t everyone know this? everyone should know this! It’s a story of connectivity and corporatization. It’s about biodiversity ceding to monoculture. And the odd intermingling of agriculture and chemical companies.

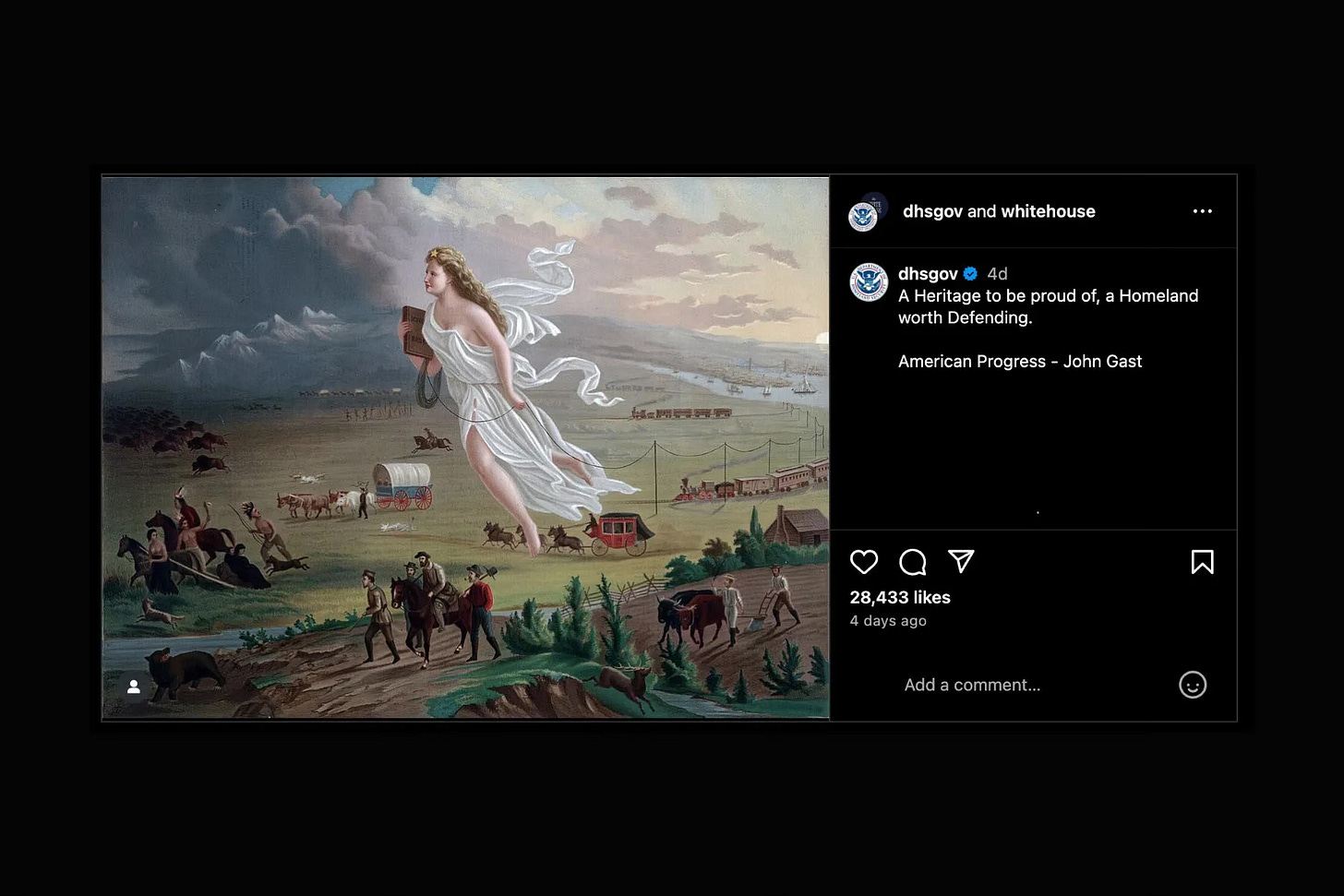

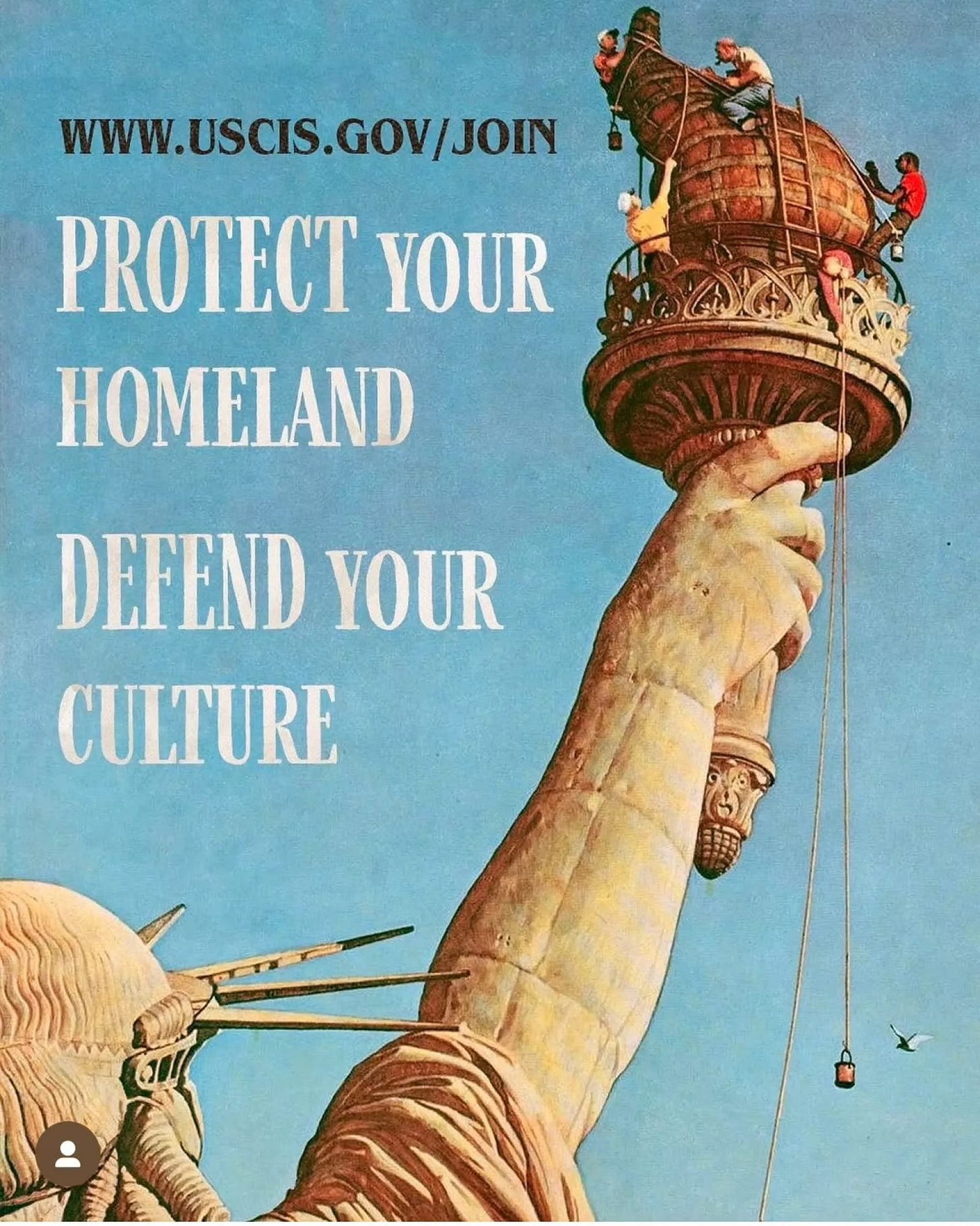

One of the reasons it has stayed with me is its undertow of similarities to the current ICE raids. The violent images of masked military figures with ridiculously large weapons and bullet proof vests yanking people off the streets is a blatant effort to rid our cities and country of diversity. While the government propaganda machine spews images and talk of “rapists and murderers and the worst of the worst” in some of its social media, it also posting old paintings — think Norman Rockwell — that depict a very white, very idealized version of “America.” Among recent Department of Homeland Security posts was a painting many of us saw in our history textbooks of America as a giant, luminescent angelic woman leading settlers west toward their manifest destiny.

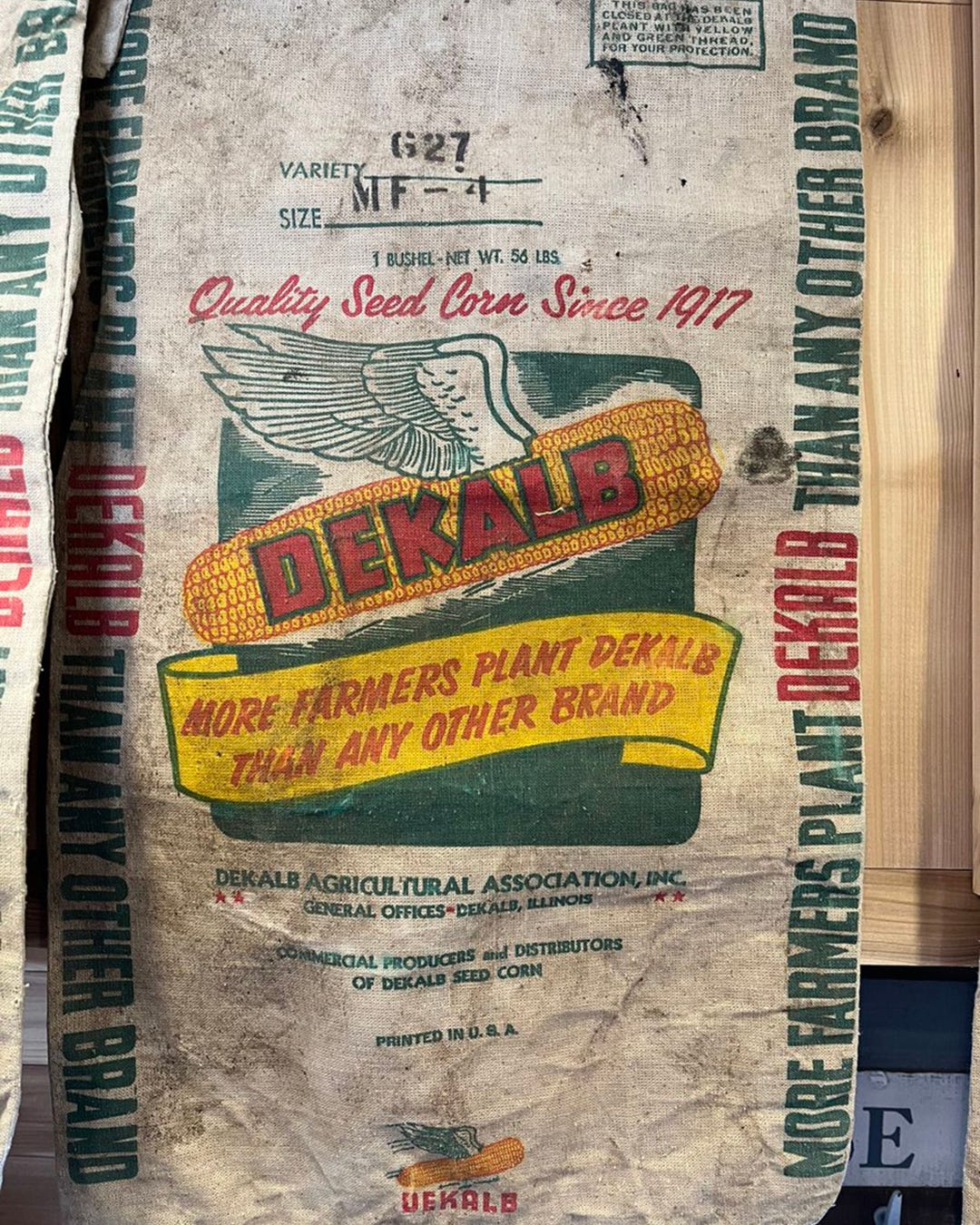

This sameness, this violence, this idealization of doing “what’s right” is what I see when I drive through fields of corn and soybeans here in Iowa. It’s what I see when I look at a logo that I used to love — the DeKalb flying corncob. This icon is shorthand for farming, a wink-wink-nod-nod to anyone who has been overlooked for living in flyover country. I nearly got it tattooed on my shoulder as a sign of Iowa pride.

DeKalb is no longer a company. It’s still a product, yes, but it’s part of the large portfolio of products owned by Bayer. And Bayer bought it from Monsanto. That folksy logo would like you to think it’s still based in Illinois and still run by the farmer-inventors who developed its eponymous hybrid seed in the early 1900s.

DeKalb had a pretty expected business mission — producing ever more resilient and productive corn and soybeans —until 1982, when it entered the world of biotech via a partnership with Pfizer. Pharmaceuticals and corn? Things were getting fuzzy.

Fuzzier still, DeKalb was bought by the chemical company Monsanto in 1996. The St. Louis-based company also got its start in the early 1900s. Its first commercially successful product was saccharin, followed by refined caffeine, vanilla extract, and aspirin.

Within decades, Monsanto was far far away from vanilla and fake sugar. During the Vietnam War, it produced Agent Orange for the U.S. military. According to the United Nations, the chemical caused an “ecocide” as 7,700,000 acres of land lost substantial tree canopy, seeds were destroyed, species declined, and exposed humans experienced increased cancer rates and birth defects.

In 1974, Monsanto patented a new product that used a chemical called glyphosate to kill weeds. A Swiss chemist had synthesized glyphosate in the 1950s for medical purposes, but it didn’t do what it was supposed to do — the backstory of so many inventions that ended up doing great harm or good. A Monsanto scientist rediscovered it, realized its potential as an herbicide, and the company patented it as Roundup.

At this very moment, millions of bottles of RoundUp are sitting on shelves at your nearest Lowe’s, HomeDepot, or Ace Hardware. A bottle might even be in your garage right now collecting spiderwebs. Many of us have had an ethical dilemma as we held a bottle of Roundup in one hand while thinking of some patch of poison ivy or invasive species that was driving us nuts. Was it worth it?

Weeds and bugs are farmers’ nemeses. I was just at an organic farming conference where one man said, “I’d rather deal with weeds than worms,” and many heads nodded in agreement. Listen to AM radio during an Iowa basketball game and you’ll hear plenty of ads that make worms and stubborn weeds sound like Marvel movie villains. Just apply glyphosate, however, and those worms will go back where they came from! Problem solved.

In 1996, Monsanto introduced glyphosate-resistant soybean seeds, followed by resistant corn seeds two years later, aka Genetically Modified Organisms. When farmers bought these genetically engineered seeds, they were buying the right to the technology behind them. That right extended to the point when the plant was harvested — no further. Monsanto told farmers they couldn’t save any seeds — an age-old agricultural practice — because doing so was tantamount to stealing the technology. About the same time the Supreme Court was granting personhood to corporations, it sided with Monsanto.

In a loop recognizable to any addict, farmers who had become dependent on glyphosate were now hooked on the resistant seeds. In a stellar and beautiful essay about corn, Robyn Wall Kimmerer ponders the ugly knotted nature of the relationship:

This is a technology that uproots the original agreement between maize and people and makes corn subservient to the needs of agribusiness. The genetic integrity of The Wife of the Sun [corn] has been compromised. There’s a word for forcible injection of unwanted genes.

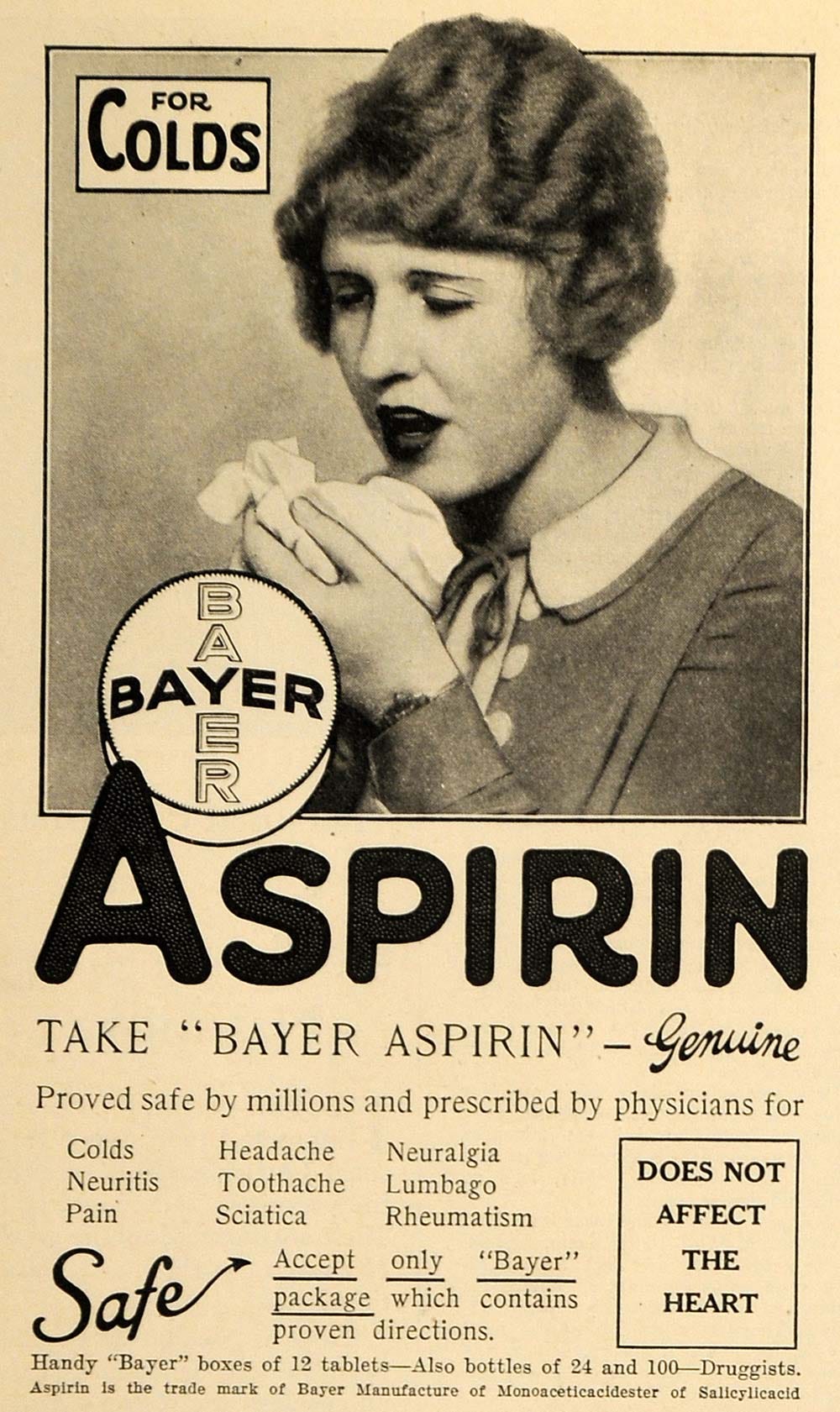

Let’s turn our attention to another company whose name you’ll recognize: Bayer. The German company began as a dye manufacturer, but its first recognizable product was aspirin, a modification of a folk remedy found in the bark of the willow plant. In the early 1900s, Bayer also trademarked and sold heroin, marketing it as a treatment for pneumonia and tuberculosis. This turned out to be a bad idea.

By the 1930s, Bayer was part of a six-company partnership under the name I.G. Farben. To access cheap labor, Farben built factories inside of concentration camps, including Auschwitz — not wholly dissimilar from today’s use of incarcerated labor to produce goods for private companies. Though Bayer now has a page of atonement on its website for this period, it undeniably benefited from its association with the Nazis and hardly turned a corner after the war.

Rather than making life-affirming products, they rolled out neonicotinoids, the insecticides that have been linked to the worldwide collapse of honeybee colonies. Bayer also went on an expansionist tear, buying up other companies and their star products, including Aleve, Alka-Seltzer, Claritin, Miralax, Flintstones vitamins, and Cutter insect repellant. In 2018, it purchased Monsanto, including DeKalb.

Drive past tall, late summer cornfields in Iowa and other Midwestern states and it’s still easy to see Dekalb signs. Bayer has wisely held onto the flying cob logo, which has a folksy vibe with undertones of red barns, overalls, and homemade noonday meals eaten on a front porch.

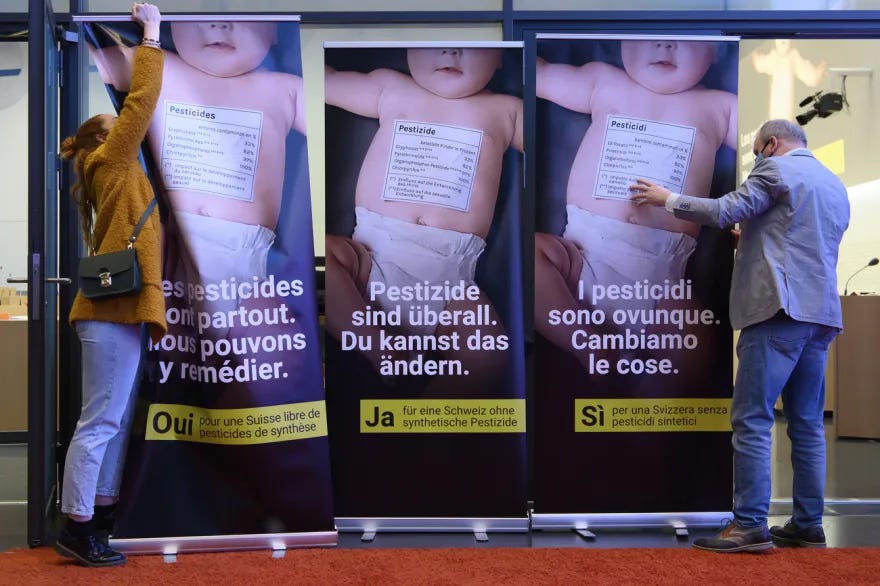

What we can’t see are the chemicals — those on the fields, those in our bodies. And we don’t see the veins and arteries that run from the fields to the bank accounts of mega corporations like Bayer. It often takes years for a cancer to surface — metaphorically and literally — but in the last decades, people have connected the dots between human health issues and the massive use of glyphosate. Some has woken up sooner than others; around 2015, countries in the European Union began to stop purchasing organic products from U.S. farmers because the amount of glyphosate allowed by the USDA was 150 times that allowed on EE crops. And this was for organic! [Source: Talk at the Iowa Organic Farming Conference by keynote Bob Quinn, University of Iowa, Nov. 17, 2015.]

According to the Lawsuit Information Center, there are currently 61,000 Roundup lawsuits against Bayer, many brought by plaintiffs claiming that exposure to glyphosate caused their non-Hodgkin lymphoma. “As of May 2025, [Bayer] Monsanto has reached settlement agreements in nearly 100,000 Roundup lawsuits, paying approximately $11 billion. Bayer achieved this through large-scale block settlements with law firms handling high volumes of claims, along with pre-trial resolutions in individual cases.”

We also don’t see how diversity has been quashed in favor of productivity — birds and insects wildly declining in numbers. The green, upright fields of summer look “normal”; most of us don’t even know how utterly NOT normal they are, having replaced the prairie, an ecosystem as diverse as the rainforest.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to liken what is happening in our agricultural and food systems to what is occurring right now in our cities. ICE deportations are a very thinly veiled attempt to “eradicate” (a favorite word of Roundup ads) anyone who doesn’t fit the dominant profile of white and Christian. Long straight rows of corn aren’t so different from the lines of ripped, groomed, white soldiers Hegseth and Trump envision. The way the government talks about immigrants is not so different than the way Bayer/Monsanto talk about weeds and worms.

If your eyes are accustomed to large scale corporate farms, an organic farm can take a minute to get used to. It’s not tidy. Bare soil is a no-no, so there are covers crops like clover that look unkempt. Two different crops are often grown together, a practice that helps reduce weeds. And the crops themselves can include plants we’re no longer used to seeing.

There are also more birds. More bees and others pollinators. Food is being grown that directly feeds humans, unlike the majority of large-scale corn and soybean farms that are producing corn to feed livestock or create ethanol.

I would much rather live next to an organic farm, just like I’d much rather live in a community that is diverse — weedy, even. I’ll take a bug-spattered windshield over a clean one any day. I’m happy when I hear many languages being spoken. When my neighbors don’t look and sound just like me.

I am so relieved my younger self thought better of that flying corncob tattoo. It’s now a sign to me of monoculture, corporate greed, and the messed up and tangled roots that comprise our current food system. There are days (today was one of them) when a visit to the local grocery store makes me sad because I can see all of these threads of chemicals and money and non-human scale decisions behind each box and bottle.

In that same essay, Kimmerer wrote: “The tools we choose to adopt influence how culture develops and also reflect a culture’s values.” Our government’s current tools are all geared toward destruction, limiting, pruning, and removal. But we need tools of creation, curiosity, and connectivity. The arts. Public education. Unapologetically drying our underwear in the breeze on a sunny day. Having a messy yard filled with dandelions.

This is really good, Jen! I want it to be in every Iowa newspaper.

Your words are powerful. 🌿 They stay with me as I think about my beloved Iowa. I agree with another comment here that this should be in every Iowa newspaper.